Contents

In this module Dr Jen O'Brien, unit lead for Creating a Sustainable World, introduces the dimensions and challenges of sustainability.

In this module Dr Jen O'Brien, unit lead for Creating a Sustainable World, introduces the dimensions and challenges of sustainability.

The module highlights the complex ways social, economic and environmental processes are linked and charts the origins and principles of sustainable development. It will also consider SDG17: Partnerships for the Goals, which supports the delivery of the other 16 SDGs, and explore what The University of Manchester is doing to be more sustainable.

All learning content for this module can be found on this page. Please use the quick links in the list below to jump to the relevant section.

1.1 Introduction: Understanding Sustainable Development

- Intended Learning Outcomes

- Definitions of Sustainability

1.2 The sustainability challenge facing humanity in the 21st Century

- The Impact of Covid-19

- Silver Linings of Covid-19

- Air Quality

- Green Recovery: Rebuilding after Covid-19

1.3 Origins and core principles of sustainable development

- The Politics of Sustainable Development

- The Triple Bottom Line: The Trade Offs of Sustainability

1.4 SDG 17: Partnerships for sustainability and the SDGs

- The Importance of Technology and Data for Sustainable Development

1.5 The University of Manchester and Sustainable Development

- The University of Manchester and the challenge of sustainability

- The University of Manchester and the Sustainable Development Goals

- Feedback

1.1 Introduction: Understanding Sustainable Development

Introduction to Core Module 01

In this video Dr. Jen O’Brien introduces sustainability and sustainable development and why now is a poignant time to study them.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

This module instils a foundational understanding of sustainability, and addresses SDG 17, Partnerships for the Goals, which supports the delivery of the other 16 SDGs.

As explained in the introduction to the course as a whole, this unit comprises 2 ‘Core’ modules, and 16 ‘Goal’ modules. The Goal modules will address specific SDG areas, like SDG 3 Good Health and Wellbeing, SDG 13 Climate Action, and SDG 5 Gender Equality. The two core modules show how organisations and people, at all scales, must work together to pool their resources and expertise to help make the world more sustainable. This is important because challenges such as global peace, equitable economic growth and climate change cannot be solved by single countries or organisations. Action is needed at a number of scales to achieve sustainability. That is why you reducing your consumption of single use plastics will have an impact on sustainability, as will encouraging the reduction of carbon emissions from the aviation industry, as will ensuring equitable access to quality healthcare, even collecting and monitoring data - to name but a few examples. That was before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. Drawing upon expert opinion we will discuss the short and long term negative impacts of the Coronavirus. Perhaps more controversially we will consider the opportunities of the pandemic for sustainability.

As you will learn in this module, sustainability is often about striking a balance between different priorities and requires trade-offs and compromises. The SDGs are important because they identify clear goals that have been agreed by almost every country on the planet and outline ways to measure progress towards targets using data. Data can illustrate the breadth and scale of a problem or issue which can then be used to inform strategic decisions, monitor impact of action and set targets. Data must be reliable, accessible and disaggregated at a usable level. This makes data expensive but, as we will discuss further in Core Module 2, and with Dr. Jonny Huck in this module, data becomes particularly important in meeting the aim of the SDGs to ‘leave no one behind’. This is why we invite you to to contribute to sustainable development data through your assignments.

After this introduction, this module contains four chapters.

- The first chapter will consider the main dimensions of the sustainability challenge that is facing humanity in the 21st century and highlight the complex ways in which social, economic and environmental processes are linked together. This chapter will also consider how the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 has impacted sustainability.

- The second chapter explains the origins and core principles of sustainable development, including the triple bottom line, approaches to decision-making and the relationship between local and global action.

- Chapter 3 focuses on SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, which outlines how we can implement and monitor sustainable development through international partnerships.

- The final chapter brings the SDGs back home, considering what the University of Manchester is doing to be more sustainable and our specific response to the SDGs.

- Intended Learning Outcomes

By completing this module you will:

- Have a grounded understanding of ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’ and the origins of the concepts

- Understand why sustainable development is essential for the future

- Understand the complexity of sustainability and sustainable development in action and how they often require compromise at multiple scales, and can be vulnerable to external threats such as global pandemics

- Begin to understand the need for partnership and good governance in sustainable development, as foundational principles for the Sustainable Development Goals

- Begin to critically reflect upon your role in sustainable development in Manchester, and beyond, and feel empowered to make positive change.

- Definitions of Sustainability

This is a course about action, doing things and making positive change. So, practising what we preach, before we begin - and without referring to Google! - please complete the exercise below. Please tell us your discipline area (for example, Maths, Geography, etc) and your definition of sustainability. For example:

Geography: My personal definition of sustainability is...

We will return to your definitions of sustainability later.

All comments are completely anonymous. We ask that you be respectful with your answers.

The below not loading? Click to refresh the page.

Take note of your own definition of sustainability. It will be interesting to see whether this changes as the course unfolds. Also have a look at a few of your colleagues’ definitions of sustainability. Is there much variety? There are two points to note here.

- Firstly, the fact that ‘sustainability’ is interpreted so differently by students studying in different subject areas illustrates one of the challenges that we face in achieving it.

- Secondly, the University College of Interdisciplinary Learning (UCIL) brings together students - or potential change makers - from across the University who can draw on different disciplinary viewpoints to reframe problems. Across the first two core modules, and indeed throughout the course, you will hear a lot about partnership and how essential it is for development. Through this course we are bringing together a vast range of different insights and skills to address issues of sustainability. That is hugely powerful.

Sustainability is a balancing act. As we declare ‘Climate Emergency’ and see the impacts of climate catastrophe and as we fight the war against single use plastics and lobby against the increasing investment into fossil fuels, there is a danger of overlooking the fact that for economic growth, for industrialisation, for energy, for the many technological and medical advances that we take for granted, even in our day to day consumption, we need to use resources. This fact is important to remember as we consider our personal impact on the world and how we might live more sustainably. Human activities take place against a backdrop of environmental systems that have changed over millennia. Plate tectonics, volcanic eruptions, varying solar radiation all generate natural changes to the climate on which our ecosystems are dependent. We need greenhouse gases to protect our earth from extreme heat and cold. The Earth’s climate has changed a number of times since the Earth formed some 4.6 billion years ago. This is why many environmental activists prefer terms such as ‘climate emergency’ or ‘ecological catastrophe’ to emphasise the fact that human impacts have massively increased the rates at which changes are taking place. As the United Nations Climate Change Agency noted in July, 2019,

“The impacts of climate change and increasing inequality across and within countries are undermining progress on the sustainable development agenda, threatening to reverse many of the gains made over the last decades that have improved people’s lives.”

United Nations Climate Change Agency

The era of industrial growth, that began in Eighteenth Century Manchester and has now spread to all parts of the planet, has generated a series of negative environmental impacts, threatening the material and human resources on which our economies depend. The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change) report of 2013, stated: “It is extremely likely [95 to 100 percent] that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.” Since the Industrial Revolution, for example, the combustion of carbon-based fossil fuels have artificially enhanced the natural greenhouse effect, preventing heat from escaping the Earth, and literally warming it up, leading to the melting of ice caps and resultant flooding.

‘Sustainability’ is about ensuring that we do not undermine our planet’s ability to sustain us. ‘Sustainable Development’ is the political project developed by the United Nations in the latter part of the Twentieth Century to strike a balance between continuing economic and human development, and the need to conserve the global ecosystems and climate upon which we ultimately depend for survival.

In the next film, Professor James Evans, Professor of Urban Sustainability, explains the difference between sustainability and sustainable development.

What is the difference between sustainable development and sustainability?

Professor James Evans discusses the difference between the closely related concepts of sustainability and sustainable development.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

As Professor Evans explained, Sustainable Development is humanity’s major global attempt to balance economic development against the need to maintain social and environmental health. It was first made popular by the Brundtland Report of 1987 and defined as:

"Development that meets the needs of the present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

Brundtland, 1987, p.43

World Commission on Environment and Development 1987, p.43

This ambition was articulated in the principle of the ‘triple bottom-line’, also referred to as the ‘Three Ps’: People, Profit and Planet. The triple bottom line begins to illustrate some of the complexities of delivering sustainability. The concept holds that all decisions in business, politics, sustainable development and so forth should take account of social and environmental impacts as well as economic gain. A new runway at an airport, for example, might open up new trade links, create new jobs and generally boost the economy of the local area. The increased aviation emissions of the new runway, however, will be detrimental to the planet. For development to be truly sustainable that negative impact on the planet needs to be mitigated. Sustainable development, therefore, sits in an equilibrium of the impacts on people, planet and profit. This is illustrated in the diagram below.

Fig 01: The triple bottom line. People, Profit and Planet.

Source: Adapted from University of Wisconsin, 2019 (online

The triple bottom line provides a framework for measuring performance of an organisation, or indeed individual, using three measurements: economic (profit), social (people), and environmental (planet) (Goel, 2010). In 2000, the Earth Charter broadened the definition of sustainability to include the idea of a global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice and a culture of peace.

As Figure 1 shows, sustainable development sits in the intersection between people, profit and planet. Emerging in the aftermath of the Cold War, the triple bottom line of sustainability represents a compromise between countries in the global north and global south that promises to allow further economic development while reducing its negative social and environmental impacts. As Professor Evans illustrated, Sustainable Development requires – sometimes politically awkward - compromise: industrialised countries have developed at the expense of the environment since before the first Industrial Revolution; imposing sanctions now on the economic growth of other countries negatively impacts their profit to the overall benefit of the planet. We will discuss this in greater detail later in this module.

The triple bottom line presents an opportunity, and a tension. It suggests that for sustainable development, which (as a reminder) shouldn’t compromise the ability of future generations to meet their needs as we develop, profit should not grow at the expense of the planet or people. The two photographs shown in Figure 2 and 3 are a good example of the tension of the triple bottom line. Leh, the capital of the Indian Himalaya is largely dependent upon tourism for its economic sustainability. That same tourism is dramatically impacting the natural world on which the economy is dependent. The economy has benefited substantially from tourists attracted to the area to look at the eco innovations that are being trialed in Leh.

Fig 02 and 03: Surrounded by the Indian Himalaya, Leh, the capital of Ladakh, is isolated by extreme weather for at least six months of every year. During this time, if possible, local residents will travel to family further south, while those that stay will spend three months preparing for the winter. Drawn by the phenomenal landscape, tourism is a hugely important source of income for Leh, a business sector upon which nearly all people depend in some way. For decades this has generated tension through the management of waste, particularly water bottles, in an effort to maintain the environment on which so many livelihoods depend. Note, the second sign has been on the landscape of the Indian Himalayas for decades.

Source: O'Brien, 2014

More optimistically, the triple bottom line also suggests that an expanding environmental agenda can, and should, integrate growth in, or benefit, social and economic spheres (Elkington, 1997). Whilst the planet delivers resources upon which many businesses depend, there are also economic benefits to being sustainable. This is powerfully illustrated by the fact that ethical investment funds have outperformed global stock market averages since the 2008 financial crisis, and that companies that reduce their carbon emissions the most outperform their peers. During the summer of 2019, the UK’s shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, announced Labour’s plans for a ‘green industrial revolution’ via an increased role for the Bank of England in regulating finance to ensure a better future for the next generations. Like many grand statements about environmental action, the declaration was a little thin on concrete detail about how to achieve this goal, but it is a notable shift in economic thinking and illustrates the increasing range of actors who are now involved in sustainable development. As we will see momentarily, global recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic offers further opportunity for sustainability through a potential ‘Green Recovery’.

From the outset, the principles of Sustainable Development as set out by the Brundtland Report in 1987, were intended to be applied in all places and at all levels, from local communities in which people live, to global decisions taken by leading nations. This idea of scaling action, and the range of actors who have responsibility for Sustainable Development, has come into sharp focus with the recent understanding of impending climate catastrophe. Many councils, including our own Manchester City Council, have declared a ‘climate emergency’, which the University of Manchester supports. This should then impact on policy making and governance to reduce carbon outputs. After decades of peaceful protests many environmental groups, like Extinction Rebellion, have now resorted to more direct action to disrupt ‘the system’, the political system, to make change that is equitable to all. Many extreme environmentalists would argue that it is too late for individual action to make an impact.

Fig 04: Inspired by Greta Thunberg, individual action became collective power as young people took to the streets across the globe in a series of climate strikes. This photograph captures a call for system change by the next generation and illustrates their power to potentially make that happen.

Source: O’Brien 2019

For sustainable development we need system change. Change in sustainability governance. Change in global energy production and use. Change in international trade and global redistribution of wealth. Meanwhile, considerable emphasis has also been placed on the idea that small actions can contribute to big impacts through the slogan, ‘think global, act local’. Chapter 4 of this module will critique what could be argued as ‘greenwashing’, and the need for informed thinking behind sustainability related behaviour. Nonetheless small actions such as reducing plastic use, recycling, eating local produce and shopping ethically, particularly around fashion (which is said to be the second highest polluting industry behind oil according to the MacArthur Foundation) can and do contribute to a more sustainable future. As David Attenborough put it in his award winning Blue Planet 2 Documentary:

“The actions of any just one of us may seem to be trivial, and have no effect, but the knowledge that there are thousands, hundreds of thousands of people who are doing the same thing, that really does have an effect, so please join us.”

David Attenborough, 2018

Blue Planet 2

Sustainable Development has been developed over the past thirty years to include a number of core principles. Often we use these terms interchangeably with little consideration of what they mean. The final exercise in this chapter is designed to encourage you to think critically about these terms.

Well done for matching up the terms. It is a simple exercise but these terms are core to understanding sustainability and they are used throughout the following modules, so it is important to understand them fully.

Why is sustainability so important? And why is it so important now? In the next chapter we will unpack some of the sustainability challenges that we face today and why we face them, in turn highlighting why it is so important to meet the global challenge of sustainable development, because, as Professor James Evans puts it:

“Love it or hate it, sustainable development remains the best shot humanity has at preventing planetary collapse at the current time.”

Professor James Evans

1.2 The sustainability challenge facing humanity in the 21st Century

The sustainability challenge facing humanity

Dr. Jen O’Brien introduces the chapter and explains how the unprecedented developments of the last fifty years have generated a number of challenges for the triple bottom line of sustainability.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

There are a number of threats facing humans in the 21st century, which are starting to jeopardise our long term survival as a species. Such has been the impact made by humans over the last few hundred years that Paul J. Crutzen, a Dutch Nobel prize-winning atmospheric chemist (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000) coined the term ‘Anthropocene’. The Anthropocene literally means the ‘human’ (anthro) ‘era’ (cene’), and denotes a geological time period in which human action has geological significance - just as the dinosaurs did in the Jurassic period. The term is yet to be formally recognised by geologists, but there is no doubt that we are facing a new period of impact. As discussed in the introduction to this chapter, we have to use resources to develop. As Emel et al., (2002:337) put it ‘Everything we use to communicate, move, stay cool, sit, sleep, cook and refrigerate comes from the 15 billion tons of raw material that humans extract from the earth each year.’ In the last 70 years we have seen a rapid increase in the use of resources due to industrial growth, often referred to as ‘The Great Acceleration’, as illustrated in Fig. 05 below.

These (now quite well known) graphs illustrate how everything, from access to telephones, international tourism, even McDonald's restaurants, has seen a massive acceleration in the last 70 years. Much of this growth has significant benefits for development. We will discuss the role of data and the digital divide a lot across the Creating a Sustainable World unit. The availability of telephones, for example, has been a source of social empowerment in poor communities by providing access to money, or healthcare, fair prices for produce, the possibility to maintain contact with family and so forth, to the extent that, even in 2010, Sachs, quoted in Etzo and Collender, suggested ‘mobile phones are the single most transformative technology for development’ (2010:661). Some academics would argue that the ‘acceleration’ is only getting faster. The Institute for European Environmental Policy argued in 2020 that more than half of all Co2 emissions since 1751 were emitted in the last 30 years, and link emissions to the need for a Green Recovery under Covid, which we will discuss later in this module (IEEP, 2020).

In the next film, Professor James Evans explains some of the key threats to the sustainability of planet Earth. As you listen to James, notice how many of the threats that he discusses are a direct result of rapid, unregulated economic growth and industrialisation, which would have once been considered beneficial advancements for society.

Key threats to sustainability

Professor James Evans examines some of the key threats to the sustainability of planet earth.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

Professor Evans argues that ‘we need to get cities rights’ as they represent challenge, and opportunity, for sustainability. By the end of this century, 85% of humanity will live in cities. Between 1950 and 2100 the population of urban dwellers will have increased from less than one billion to nine billion (OECD, 2015). Many researchers will argue that the main consequence of the rapid growth of cities is that sustainable development, economic growth, social inequality, climate change and health are increasingly urban challenges (Bai et al. 2018; Short, 2017). In turn, if we can make cities sustainable, healthy and equitable, then we will have gone a long way to fixing many of the problems that we, and our fellow species, face. This is why the United Nations formulated a specific goal around Sustainable Cities and Communities, SDG 11. The goal recognises that while cities are part of the sustainability problem, with a mass of people all drawing upon resources to eat, drink, dispose of waste, stay healthy and so forth, they are also the most effective places to implement solutions. This is illustrated by Figure 6 below, which shows the lights of incredibly densely populated Hong Kong whilst coming in to land for a sustainability conference (yes, the irony is palpable). A mass of people all together poses greater resource pressure but enables greater efficiencies in delivering power, for example, or removing waste. Much less land is used when buildings go up rather than out, perhaps enabling greater green space. Cities also become interesting sustainability test sites, the classic examples being Masdar in Abu Dhabi, believed to be one of the world’s most sustainable urban communities. As we will discuss momentarily, cities have become even more complex spaces under Covid-19.

Fig 06: The urban density of Hong Kong allows for efficient use of space and delivery of services such as water and power.

Source: O'Brien, 2015

Moreover, the challenges that Professor Evans outlined earlier are catalysed by climate crisis. The Environmental Justice Foundation estimates that globally, 41 people are being displaced each minute. The Global Report on Internal Displacement (2016) found that between 2008 and 2016 21.5 million people were displaced due to climate change – and that rate of change is increasing dramatically. Climate change can be a key driver of humanitarian crisis or it can make an existing crisis worse. Such crises then tend to be under reported. Care International (2020) refer to Africa as a ‘blind spot’ for the coverage of humanitarian crises that are fuelled by the climate emergency. In 2019 Madagascar suffered a chronic food crisis due to drought that impacted 2.6million people but this crisis largely went unknown internationally. Of the US$90bn damage created by Hurricane Harvey that ripped through the Caribbean and Texas in 2017, around US$67bn is attributable to the human influence on climate (Frame et al., 2020). The catastrophic bushfires in Australia in 2020 not only destroyed 5.4m hectares of rainforest, home to 3,000 indigenous people, but released 830m tonnes of carbon dioxide, far more than the country’s annual greenhouse gas pollution (New South Wales Environment Department, 2020). California governor Gavin Newsom declared that the wildfires that swept through California in the summer of 2020 show that the ‘debate around climate change is over’ (BBC, 2020). Rates of recovery will be impacted by climate changes including drought or more frequent and intense fires. Whichever example you draw upon from the perspective of the subject that you are studying, there is no doubt that:

“The impacts of climate change and increasing inequality across and within countries are undermining progress on the sustainable development agenda, threatening to reverse many of the gains made over the last decades that have improved people’s lives”.

United Nations Climate Change Agency, 2019

Drawing upon Professor Evans’ thoughts about the challenges for sustainability, and your interpretation of ‘sustainability’, so far, what do you think? Are we doomed? Can we avert a global collapse before 2100? The next exercise invites you to tell us, and each other, what you think. After you’ve completed the poll, you’ll be able to see how others taking the unit have voted. We will also ask you to complete the poll again at the end of the course.

What did you make of the responses others made to the poll? Did most people vote the same way as you? Did they think differently? And what did you think about being asked the question, ‘Are we all doomed?’ at the start of a unit about sustainability?

As you have probably already begun to appreciate, and perhaps have experienced yourself, the sustainability challenges that we have faced, arguably since the Brundtland report of 1987, are interlinked - in turn generating difficult questions as to how they could, or should, be tackled, as Professor James Evans outlines in the next film.

How sustainability challenges are interlinked

Professor James Evans explores how the challenges of sustainability are interlinked, and what that means for tackling them.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

Appreciating the interlinkages between the different components of sustainable development generates tensions and opportunities as to how they should be tackled. In particular it highlights the need for partnerships between different actors at different scales, whether that be reducing aviation emissions, reducing single use plastics, or regulating the banking sector, as no single group, country or organisation can fix these problems in isolation. This need for new partnerships and better governance is a core part of SDG 17, which we will discuss further. Before that, the following exercise invites you to consider some of the interlinkages between key sustainability challenges to illustrate the complexity of the sustainable development challenge that we face.

- The Impact of Covid-19

We have begun to outline the complexity of the challenges that we face in sustainable development. That was before the Covid-19 pandemic. A number of recent global disasters have been exacerbated by Covid: providing shelter for families who have lost their homes to wildfire, or are seeking asylum having crossed the channel, is much harder to do when social distancing is required. In the next film, Professor Evans talks about the impact of Covid-19.

The impact of Covid-19

Professor James Evans explains the impacts of Covid-19 for sustainability and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

James talks about the ‘triple hit’ of Covid-19 on progress towards sustainability. He identifies challenges to work, health and education, which have led the UN to say that Covid 19 will reverse the last ten years of global development. We will hear more about the challenge of Covid for the SDGs from Professor David Hulme, in Core Module 2.

On top of the direct impacts of Covid, in the next film, James explains how Covid has further exacerbated existing inequalities, creating challenges that cut across the SDGs. The digital divide is an immediate example, and one that we will discuss further in SDG 9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure.

The impact of Covid-19 on existing inequalities

Professor James Evans discusses further impacts of Covid-19, and the challenges these present for the SDGs

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

In the film, James explains how progress towards gender inequality has been reversed. SDG 5 Gender Equality considers the global patterns of gender equality. It’s interesting that James focuses on examples from the Global North, where women undertook greater childcare responsibilities during lockdown, shifting the shape of the workforce, potentially with long lasting implications.

- Silver linings of Covid-19

We mentioned earlier that cities present a curious space for sustainability as perpetrator and victim of, and potential saviour for, sustainability. Covid 19 has reshaped cities with some unforeseen but positive consequences, as James explains in the next film.

Silver linings of Covid-19

Professor James Evans discusses some positive consequences of Covid-19, from reductions in air pollution to changes in public attitudes to the environment

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

In the film, James mentions the reduction in emissions from the aviation industry. To put that into perspective, let’s consider carbon footprints. An individual’s carbon footprint is an estimation of the amount of CO₂ given out as we travel, buy food, heat our homes, and generally live. The average personal footprint in Britain in 2013 was 7.1 tonnes (t). To reduce environmental impact in line with the IPCC’s report, individual carbon footprints must be reduced to 1.2t of CO₂. On every flight to New York and back, each traveller emits about 1.2t of CO₂. According to the IATA, the aviation industry contributes roughly 2% of global CO₂ emissions, which equates to approximately 815 million tonnes of CO₂ globally. Moreover, air travel emits other vapours and gases that contribute to the greenhouse effect with the IPCC estimating that the warming effect of aircraft emissions is about 1.9 times greater than CO₂ alone. Due to a Global Agreement from 1944 to facilitate trade, there is no tax on aviation fuel. A decrease in air travel at the start of lockdown, then, was a good thing. Le Quéré et al., (2020) estimate that at their peak, emissions in individual countries decreased by –26% on average. Of course, the related implications of decreased air travel are job losses both directly and through the impact on associated industries.

James also touched upon how patterns of behaviour have changed, positively and negatively. The image below shows a graph of the electricity use in University Place. The blue bars show usage in July-early September 2020, while the red line shows usage in the same period in 2019, and the orange line the University’s ongoing target to reduce electricity use by 1%. Note the shift in 2020 usage at the point when University buildings began to be used again after lockdown. While it’s a good thing that the University’s electricity use decreased during the 2020 lockdown, the overall net energy use will have shifted, potentially onto people for whom energy is already expensive. We’ll discuss Energy poverty in more detail in SDG 7 Affordable and Clean Energy.

Fig 07: Energy output from University Place, The University of Manchester

Source: University of Manchester, 2020

Activity

You can track the heat, water and electricity use of all University of Manchester buildings on the University’s Energy Dashboard, using the link below. Use the links at the top of the screen to search by building or School.

Have a look at the buildings you use most often. Are there any notable trends? Before lockdown, how close was your building to reaching its 1% energy reduction target?

Lockdown changed many of our local habits, to the benefit of sustainability. For example, carbon emissions in the first half of 2020 are likely to be 14% lower than they were for the same period in 2019, because spending remained weaker than usual even as lockdown restrictions eased (Guardian, 2020). The clothing industry is one of the greatest contributors to carbon emissions, so lower spending on clothing may have cut emissions from clothing stores by 620,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Remember the triple bottom line again, though: the challenge here is the hundreds of thousands of low paid workers in the garment industry who lost their jobs as international contracts for clothes were cancelled due to low demand. Now, think back to James’ point earlier about the impacts of Covid-19 on inequality: often the workers who lost their jobs were women who relied on the flexible work to fit around childcare. The World Bank estimates that the pandemic could increase the number of people who are extremely poor (defined as living on less than USD1.90 a day) by 71 million to 100 million (World Bank, 2020).

- Air Quality

James also talked about how air quality improved over cities during the Covid 19 pandemic due to the reduction in traffic during lockdown. If you live in a city, maybe you noticed this yourself. For a while, at least, the air smelt better.

Arguably air quality is under-represented in the Sustainable Development Goals. It’s given just one short mention under SDG 3, which is one of the broadest SDGs, though the consequences of air pollution extend beyond health: particulate matter in the air also damages ecosystems through acidification, for example. In our SDG3 module, Professor Sheena Cruickshank discusses the health impacts of poor air quality. Just 20% of the urban population studied by the World Health Organisation (WHO) live in areas that comply with WHO air quality guidelines levels of PM 2.5 . PM means particulate matter and can include any particles in the air, from car exhausts to pollen. Poor air quality has long been recognised as a major health challenge. In cities in the global south, particulate air pollution can be 4 to 15 times higher than WHO guidelines which put many people at risk of long-term health problems, arguably in places that have huge pressures on existing under-resourced health care infrastructure - and that was before Covid-19, which has heightened the problem or air pollution, and the awareness of it. Now, evidence suggests that there are links between transmission of Covid-19 and poor air quality, which is often found in poorer areas, such as on arterial routes into city centres.

It is now clear - literally in the air - that any temporary improvement in air quality achieved during lockdown has been lost, as people have started using their cars again. Meanwhile, early research indicates that Covid particles have been found on air pollution and, of course, it is harder to recover from a respiratory disease like Covid-19 if you are breathing poor air, and Covid-damaged lungs will be heavily impacted by air pollution. Clean air then becomes more than ever an imperative for sustainable development and, as James suggested, another opportunity to make more people listen to sustainability concerns.

Further Study

Air pollution impacts us all. To illustrate this, click on the links below to access live local data from Air Quality England and the Manchester Urban Observatory. Both of these platforms enable you to see how many times in each month the air quality – the air that you are breathing – exceeds the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines of poor quality.

This Guardian article provides an accessible summary of findings to date about Covid-19 in air pollution:

While this article from The Independent features one mother’s very personal story of the impacts of air pollution:

Manchester is the second-worst council area in England for inhalable particulate matter and thought to be the most congested region outside of London, with 152 roads in breach of legal NO₂ levels. Manchester’s Mayor, Andy Burnham pledged to make Manchester a leading green city in Europe, investing £122m in a Bus Priority package and £83 m on 27 new trams whilst trebling the number of electric vehicle charging points and delivering 40,000 more seats on commuter trains as part of his ‘Congestion Deal’. At the same time £6 billion has been invested into road plans.

However, Manchester’s proposed ‘Clean Air Zone’ has been continuously delayed, most recently due to Covid. It is a controversial plan that has been challenged by commercial drivers, particularly smaller businesses, who will be taxed to drive into the city centre. Environmental groups have argued that not charging private vehicles means the plan will be insufficient to improve air quality, while others have argued that taxing private vehicles will disadvantage the poorest in society. This latter argument has been challenged, as ONS data illustrates less than 10% car ownership in the lowest income households, whilst nearly all households in the richest 10% by income own a car. Meanwhile, air quality campaigners argue that even if the clean air zone was brought in tomorrow, a newborn baby would be five before they would breathe legally safe air. Like any sustainability problem, there are competing positionalities, not least from taxi drivers who argue that the tax imposed on their vehicles will make their business unviable.

Activity

The newspaper articles below provide a useful summary of the environmental debate around Manchester’s ‘Clean Air Zone’, and the subsequent shifts in the discussion under Covid-19. The positionaility of taxi drivers is particularly interesting. Read the articles, then answer the questions that follow.

- Drivers in Manchester may face charges under mayor’s clean air plan (PDF version)

- Burnham criticised over exemption for private cars from clean air charge (PDF version

- Greater Manchester Clean Air Zone is delayed again (PDF version)

- Hundreds of taxi drivers plunged Manchester city centre into traffic chaos… (PDF version)

What do you think?

- Should we tax private cars to travel into the city centre of Manchester in effort to reduce air pollution?

- Is it fair to tax business vehicles?

- What are viable alternatives to driving into the city and how accessible are these, to everybody?

- Could - or should - Covid help to catalyse this action?

In the ‘Silver linings of Covid-19’ film James also outlined how Covid-19 has changed people’s attitudes towards the global environment. As he explained, some evidence from opinion polls suggest that people are more aware of climate change as a threat because, for the first time ever, they are part of the crisis. Air quality is a question of sustainable development. As truly awful as the Covid 19 pandemic has been, the opportunity for health if we can reframe these questions, make them more accessible and more clearly positioned on political agendas, is one potentially good outcome.

Activity

Many sources recognise that some of the sustainability changes that occurred during lockdown are ironically unsustainable - there is an accessible report:

Others, such as our own Policy@Manchester, have identified how Covid has exacerbated the interlinkages of sustainability challenges:

Have a look through the research and policy recommendations and consider:

- How has Covid impacted cities, positively and negatively?

- How does gender link to work and how have these inequalities been accentuated by Covid-19?

- Who is responsible for policy to bring about change?

- Green Recovery: Rebuilding after Covid-19

Covid-19 has shown us a need for Green Recovery that would facilitate rebuilding our economy and society but with respect to the environment to facilitate a more sustainable future. Jonny Sadler is the Director of the Manchester Climate Change Agency. You’ll hear from Jonny in SDG 13, Climate Action. Here he summarises the the opportunity afforded by a green recovery:

‘A green recovery is partly about making sure that we get on track to meet the objectives of the Paris agreement, but it's also absolutely about improving health and wellbeing in our cities. It is about boosting business. It is about creating good secure green jobs. So there are lots of very good non-climate reasons, if you like, why we would want to have a green recovery within this city and around the world.’

Jonny Sadler

Earlier, James made the point that due to Covid-19, governments are more willing to legislate to encourage healthy behaviours but also to discourage unhealthy behaviours. Jonny’s positioning of a green recovery further illustrates the need for stronger partnership between different actors. This is challenging when you look at the intersectionalities of sustainable development and realise the need for multi-scalar, multi-actor governance to address them. There is no ownership of air, for example; it is a commonly held resource. Air crosses international boundaries, especially as aircraft travel overhead. No global government exists to fix these global problems. While we may end up with a global government at some point in our species’ future, it is unlikely to happen before the end of this century, which is the critical time frame to ensure the sustainability of the planet. The best solution we have is for people and organisations to work together, which is what the SDGs are all about. The enabling mechanism enshrined in SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals proposes ways to strengthen governance, or the ability to organise collective action, for sustainability. Of course, the key question then becomes who should be acting to fix our global problems?

In the next Film, Professor James Evans talks about how we might rebuild in a more sustainable way after Covid, and who should make this happen.

Sustainable rebuilding after Covid-29

Professor James Evans talks about what sustainable rebuilding might look like: clean energy, a supportive political climate, global thinking and partnership

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

James made the point that global problems require global solutions for sustainable development. Before we address the important question of responsibility for sustainable development, we need to unpack sustainable development in a little more detail and explain why global cooperation has been such a challenge in the past. The next chapter considers where sustainable development has come from and explains some of its core principles.

1.3 Origins and core principles of sustainable development

Origins and core principles of sustainable development

Dr Jen O'Brien introduces the chapter, which outlines the origins of Sustainable Development.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

So far in this module we have introduced sustainability and sustainable development and presented the concept of the triple bottom line laid out by the Brundtland Report. In the last chapter we discussed why sustainable development is needed by beginning to unpack the sustainability challenges that we face today and where they have come from. This chapter will deepen our understanding of sustainability, and its relationship to the more political concept of sustainable development and consider some of the political milestones that have shaped the agenda.

To begin, in the next film, Professor James Evans explains where the idea of sustainable development came from.

Where did the idea of sustainable development come from?

Professor James Evans explores the history of the idea of sustainable development.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

If sustainable development is an attempt to enable development to continue while not endangering the long term sustainability of the planet, as Professor James Evans explained, it is a highly political concept, which illustrates why the global collaboration necessitated by Covid-19 is such a shift in governance. This is powerfully illustrated through the two WorldMapper examples in the interactive below.

Using the slider arrows between the two images, slide to the right to look at a world map showing the size of countries relative to their Global CO₂ Emissions in 2009. Slide to the left to see a second map, showing the size of countries relative to the number of participants they sent to the UN Climate Change Conference in 2010. Comparing these maps suggests that, with the exception of Western Europe, the countries emitting the most carbon seem to be the ones least concerned by climate change.

The chart below, taken from Our World in Data, illustrates the measure of cumulative CO₂ emission given as the share of the global total. The graph clearly illustrates the significant transitions and shifts in global emissions which have occurred. If you click on the interactive version you can see the emission shifts of individual countries over time. You’ll notice how, for most of the 19th century, global cumulative emissions were dominated by Europe; firstly in the United Kingdom, and then other countries in the (now) European Union. You’ll notice also that the cumulative contribution of the United States began to rise in the second half of the 19th century into the 20th. By 1950 its contribution peaked at 40 percent; since then it has declined to approximately 26%, but remains the largest in the world. Look also at emissions for China and India. By 2015, China accounted for 12% of total cumulative emissions, and India for 3%.

Source: Our World in Data

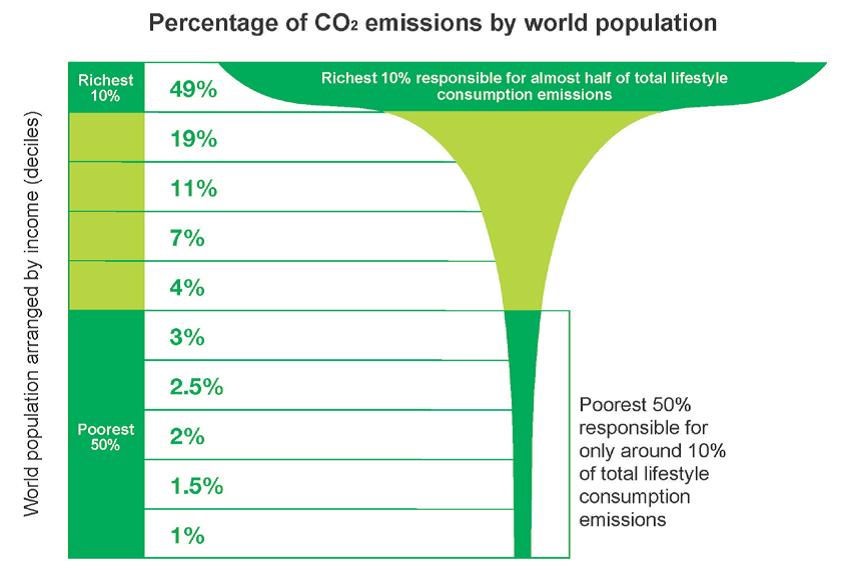

In 2015, a report from Oxfam highlighted how there is a challenge of fairness and inequality in sustainability, with the wealthiest 10% of the global population being responsible for 50% of emissions. This is illustrated in Figure 8, which illustrates the percentage of CO2 emissions by world population. In stark contrast to the richest 10%, the poorest 50% are responsible for only around 10% of total lifestyle consumption emissions.

Fig 08: Percentage of CO2 emissions by world population.

Source: Oxfam

Figure 8 illustrates the political awkwardness around sustainability policy that Professor Evans mentioned earlier. The richest 10% of the population are responsible for almost half of the total lifestyle consumption emissions whilst the poorest 50% are responsible for around 10% of the emissions. Already we are seeing the physical consequences of these emissions through, for example, the cyclones that hit Mozambique in the summer of 2019. Not only are the populations that are least responsible for the emissions still being impacted by them, but also, because they are also poorer, they are generally the populations who have the fewest resources to mitigate or respond to that crisis.

Fig 09: Taken at the March 2019 Youth Strike for Climate

Source: O'Brien, 2019

- The Politics of Sustainable Development

Whether it is considered through international carbon emissions, the aviation industry, or quotas of fish, sustainability is inherently political. Sustainable Development therefore requires wide political buy-in. Many countries have signed agreements based upon the principles of sustainable development, as James explains in the next film.

Partnership in Sustainable Development

Professor James Evans introduces the importance of partnership in Sustainable Development.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

As a political concept, Sustainable Development has been recognised in global governance for several decades. There are many sustainability timelines to be found on the internet. It is interesting to note the point at which the different synopsis of sustainability start and which key events they include, which often reflects the positionality of the creator of the source. A key milestone in environmental action was the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. This was the first time that the political world came together, not only in multiscalar partnership but in recognition of the imperative of climate in Sustainable Development. This partnership led to the establishment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which, as the next section outlines, went on to build the COP 21 in 2015 as a governing framework for climate emergency as agreed by 187 Nations.

From Rio to COP21

Fig 10: Rio Earth Summit, 1992

Source: United Nations (online)

The first major climate conference was the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. In the first global statement of the need for partnership for the Environment ‘Rio’ welcomed hundreds of thousands of people from all sectors into the decision making process to reach the action plan Agenda 21, more commonly known as the ‘Rio Declaration’. This was an agreement between 172 states and a wide-ranging blueprint for action to achieve sustainable development worldwide. At its close, Maurice Strong, the Conference Secretary-General, called the Summit a “historic moment for humanity” as governments recognised the need to redirect international and national plans and policies to ensure that all economic decisions fully took into account any environmental impact – essentially adhering to the triple bottom line of sustainability.

Fig 11: COP01, 1992

Source: United Nations (online)

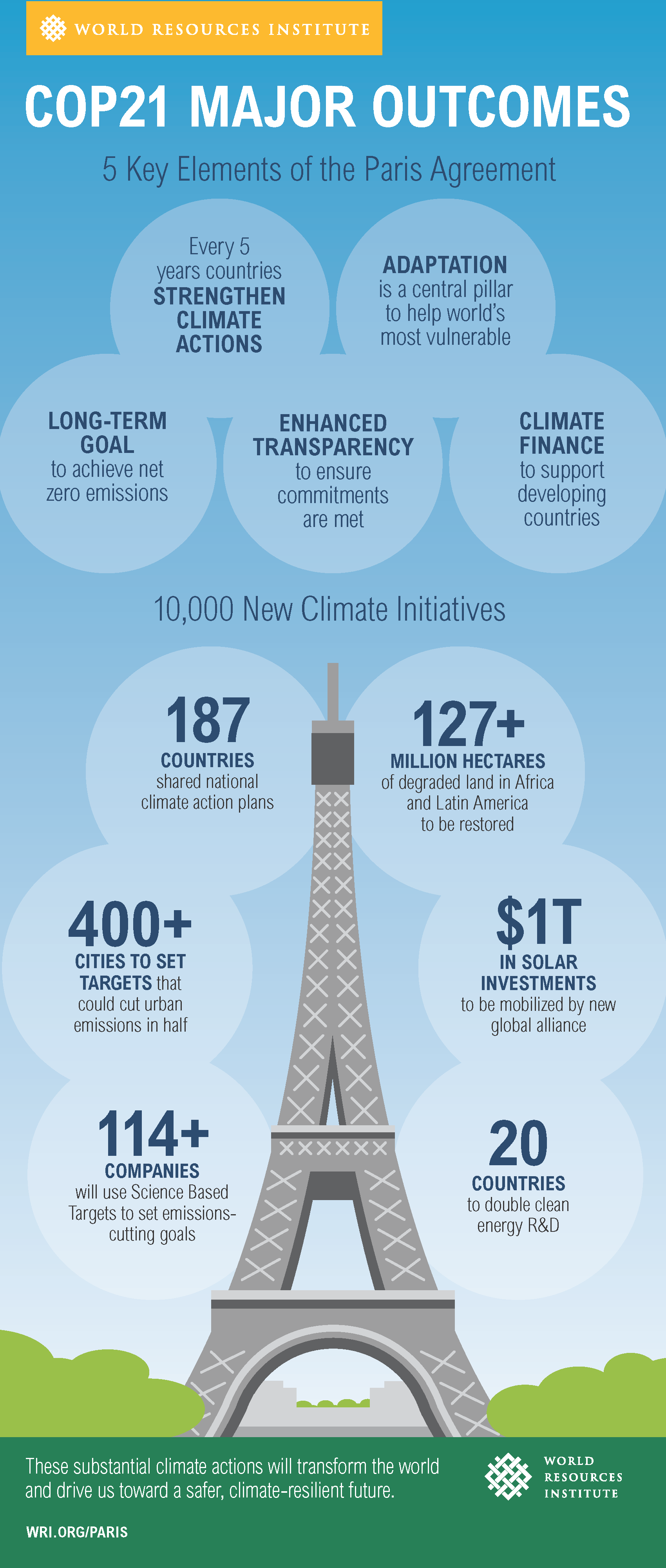

Building on the success of the Earth Summit, countries were invited to join the UN’s United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC was designed to cooperatively consider what could be done to limit average global temperature increases and the resulting climate change, and how to cope with the impacts. The UNFCCC meet annually. The Paris Agreement, also known as the COP 21 (2015), built upon the Convention on Climate Change.

Fig 12: COP21, 2015

Source: World Resources Institute (online) Summary of the agreements of the COP 21

The Earth Summit at Rio, which led to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was a statement of action. For the first time all Nations were united to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its affects. This commitment was declared in the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal known as the Paris Agreement. Enhanced support was offered to assist countries in the global south, or still ‘developing’, to do so. The central aim of the Paris Agreement is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The collective progress towards the COP is assessed every 5 years. (Remember our earlier discussions about the aviation industry and Manchester Airport meeting the expectations of the Paris Agreement)

As explained earlier, the UNFCCC meets annually. The 2019 meeting of the UNFCCC was held in Bonn amidst the soaring heatwave, perhaps the tangible result of historic unsustainable practices. The conference showcased best practices of effective climate policies and technologies and stressed the need for nations to deliver on the mandates agreed in Paris in 2015. Amidst the extreme heat of Bonn in 2019, Ms Espinosa, UNFCCC Executive Secretary, stated:

“We can no longer afford incremental progress when tackling climate change – we need deep, transformational and systemic change throughout society which is crucial for a low-emissions, highly-resilient and more sustainable future.”

Ms Espinosa, UNFCCC Executive Secretary

At this meeting, it was recognised that in order to achieve the central Paris Agreement goal of holding the global average temperature rise to as close as possible to 1.5 degrees Celsius, greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced 45 per cent by 2030, and climate neutrality achieved by 2050.

- The Triple Bottom Line: The Trade Offs of Sustainability

As we’ve seen, the idea of sustainable development has existed for more than thirty years, forming the focus for numerous global conferences and thousands of policies aimed at protecting the environment. That said, our planet is arguably in a worse state than ever before, and many criticisms have been levelled at the idea of sustainable development. These range from neo-malthusian arguments that population growth has been too great to sustain, through to radical arguments that the insistence of capitalism on economic growth is fundamentally incompatible with sustainability. While these critiques (and others) undoubtedly contain some truth, they are best viewed as challenges to be overcome as they provide no realistic global alternative.

One of the key weaknesses of sustainable development has been the difficulty of achieving real change and ensuring that economic growth does not harm the environment. In practice economic interests often trump social and environmental considerations. In part this reflects the difficulties of putting financial valuations on social and environmental impacts so that they can be directly weighed up against economic benefits. For example, it is easy to estimate the economic benefits of a new housing estate, but harder to capture the cost of destroying the small wetland on which it will be built. Valuing more sustainable development options is also complicated by the fact that sustainability benefits tend to be longer term and more diffuse than economic benefits. For example, as we discussed earlier, the benefits of building a new airport are immediate in terms of extra economic activity, investment and jobs, while the environmental benefits of not building the airport are exceptionally long term and relate to things as diverse as avoiding coastal flooding in Bangladesh, reduced heatwaves in Australia and fewer fires in the Peak District. In practice there are multiple trade-offs in decision-making around sustainable development and sustainable action.

Lets look at two tangible, interlinked examples of the need to consider trade offs in sustainability at an individual level; plastics and food.

Plastics

In part due to the work of Sir David Attenborough in the Blue Planet series, most people are aware of the damage that plastics have created on the earth. But plastic is a wonder product, the value of which has to be weighed up (or traded off), against the environmental destruction created by poor use and disposal of the waste, largely generated by our throwaway consumer culture. Plastic needs to be understood as an important resource. In the next film, Michael Shaver, Professor of Polymer Science, explains the science and background of plastics.

What are plastics?

Professor Michael Shaver explains the science and background of plastics.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

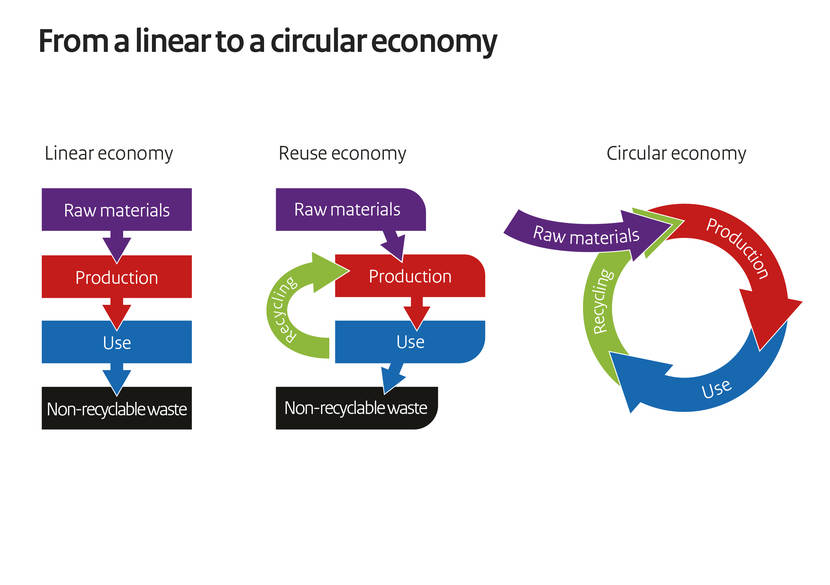

As Professor Shaver explained, plastics transformed our ability to manufacture things and dramatically reduced the costs of production which in turn reshaped us as consumers. Plastics made many more consumer goods much more accessible because they became affordable. Plastics are efficient in every way and in fact, actually have a low economic footprint to produce. The challenge is what to do with them at the end of their lives. This is where the physical materiality of the plastic represents a cultural and governance issue as less planning was invested into how to dispose of the wonder product.

Moreover, plastics are not the same. Plastic packaging is made from seven different types of plastic, some of which are more recyclable than others. The heavier the packaging, the more protective it is but the harder it is to recycle. Nobody would challenge the necessity of plastics in technology or medicine, but a tougher question is generated in relation to food waste. For example, what are we to make of reports that an unwrapped cucumber will last for three days, assuming it survives transport to a supermarket, while a shrink wrapped cucumber will last for around 14 days? According to Fareshare, 1.9 million tonnes of food is already wasted in the UK every year. That’s a huge resource loss, before you consider the multiple costs of production, transportation, processing and so forth. Packaging means that only 3% of food goes to waste before it reaches the shops. Most supermarkets now charge for single use plastic bags. A Danish report on the life cycle of plastic bags published in 2018 concluded that the more sturdy ‘bags for life’ that are made from non-woven polypropylene are only less damaging to the environment if they are used 52 times. An organic cotton bag needs to be used 20,000 times (that’s a shopping trip every day for over half a century) to balance out the resources required to make it.

Plastic itself is not the problem. The issue is how we use plastic and the type of plastics that we use, precisely because the wonder product is so cheap to make and versatile. In the next film Professor Michael Shaver discusses how and why plastics have become so vilified as an environmental problem and what we need to do to reduce the negative impact of plastics.

Plastic is not the problem

Professor Michael Shaver explores why plastic itself is not the problem.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

Did it come as a surprise to hear Professor Shaver say we should use more plastics? Plastics have a low carbon footprint, certainly when compared to glass or paper, but they have to be the right plastics. Whilst stressing the need to just produce less waste, Michael indicated the difference between ‘able’ and ‘ed’ words, so rather than using recyclABLE plastics, we need to use more recyclED plastics. That requires, however, a policy shift that enables us to more effectively treat and recycle plastics, and indeed all waste. This argument still supports the ‘war against plastics’ that is such a popular environmental message at the moment, but illustrates a need for a more nuanced, or critical, understanding about plastics. In the next film, Professor Shaver illustrates the role of the individual in a better understanding of plastics but also the need to critically challenge some of the environmental messages that we are exposed to, particularly through the popular media.

Understanding what you buy

Prof Michael Shaver talks about the role all of us can play, by making sure that we understand what we buy, and what happens to the product when we’re finished with it.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

There are always trade-offs in sustainability. As Professor Shaver said, you have to be well-informed about the decisions that you are making. Sometimes this requires challenging the popularist message, or going a step further to understand the reality. Often this has policy implications. When we were talking after the interview, for example, Michael referenced how the widely used Vegware take away cups are technically recyclable. But, few councils have the ability to recycle them, so they are often sent to landfill. As the consumer you think you are using a recyclable cup. Let's look at another very poignant example of sustainability trade offs and misunderstanding. Food.

Food

The photograph below was taken at one of the first Youth Strikes for Climate in Manchester. The prominent ‘Go Vegan’ sign was offered as a major solution to climate catastrophe.

Fig 13: This was the first Youth Strike for Climate held in Manchester. The ‘Go Vegan’ sign was a dominant backdrop for hundreds of young people who were on strike from school to make a statement of the need to address climate catastrophe.

Source: O'Brien, 2019

Being vegan is becoming more popular as the health benefits of a plant based diet are increasingly recognised, even to the benefit of business making it a much easier diet to follow as vegan options are now readily available in a number of restaurant chains. But echoing Michael’s words about a more critical understanding of plastics, as an environmental action the message that a vegan diet will reduce climate catastrophe needs some careful consideration.

In the next film, Dr Malte Rödl, who is an Engineer, talks about a vegan diet and the complexities and trade offs of eating sustainably. Returning to the opening discussion in this module, Malte first challenges you to consider how you would define ‘sustainable’.

Eating sustainably

Dr Malte Rödl explains the complexities and trade offs involved in eating sustainably.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

As Dr Rödl explained, broadly speaking, a vegan diet causes around 40% less green house gases (GHGs) than a diet including meat, dairy, and/or other animal products, which has been verified by much research such as Aleksandrowicz et al., (2016). A vegetarian diet still emits around 25% less GHGs. But as Malte explained, it is important to consider the full scope of sustainability: think back to the triple bottom line of people, planet and profit. Food is actually really quite complex when it comes to sustainability.

Malte talked about the impact of diet on the planet, for example, which is much greater than carbon alone. The monocultures of maize and soy in the Americas grown for tofu, meat alternatives, even animal feed, require a huge use of fertiliser, pesticides, and herbicides, which may cause among others biodiversity loss, eutrophication, or even illness of farmers. In the worst cases, native rainforest was logged or burned to create those fields.

The transportation of food is often under considered. Locally or regionally grown food needs less transport—but these benefits are quickly equalised or destroyed when foods are instead grown in passive or active greenhouses; Clune, et al., (2017) suggest that heated greenhouses increase the GHGs of fruit and vegetable production six fold. If products are harvested far away from consumption, the mode of transport matters. The least impact is associated with cargo ships, the most with aeroplanes (see Edwards-Jones, 2010). This is particularly important for products harvested far away that need to be kept cooled in shipping containers or trucks: Green beans flown in from Kenya to England might be cheaper, but emit around ten times more GHGs than green beans grown in the UK. As Malte highlighted in his tomato example, heated greenhouses may still be preferable but then a tomato grown in a heated greenhouse in the Netherlands will have a higher carbon footprint than one grown in the sunshine of Spain but flown to the UK. Perhaps surprisingly, tropical fruits such as pineapples generate 98% of their GHGs through transport. Eating only what is in season, ideally as close to home as possible, reduces the choice of fruit and vegetables to a lot of kale, cabbage, and root vegetables in British Winter.

Take a look at the chart in Figure 13 below, which demonstrates that cows milk has a higher environmental impact than vegan substitutes.

The chart shows that, whether we measure in terms of carbon emissions, land or water use, milk alternatives are better for the environment than the real thing. But focus in a bit more closely, and maybe things are not quite so clear cut. Almond milk has a much lower carbon footprint than semi skimmed dairy milk, but almonds also require huge amounts of water, around 5 litres per almond. In California, where over 80% of almonds are grown, drought has raged for decades. Wat does that say about the sustainability of almond milk? In a more ‘social’ example, the demand for the superfood quinoa has been blamed for many local farmers in Peru and Bolivia not being able to afford their native grain. You might have personal reasons for dietary choice, which are essential for you, your health, culture and your lifestyle, but without critical consideration, just going vegan won’t necessarily save the planet.

Try it for yourself. For our next activity use the climate change food calculator to analyse your own diet, thinking critically about the multiple dimensions of sustainability that we have discussed.

Activity

Consider your own dietary preferences, as situated in the real life context of access, availability, cost, food needs (all of the triple bottom line). Use the carbon footprint calculator below to reflect critically on the sustainability of your, (and your family’s) diet.

As you use the calculator, consider the following:

- Did the environmental impact of any of your usual foods/drink surprise you?

- Is measuring carbon footprint the most helpful way to understand the sustainability of food?

- Could you make any (sustainable) changes to make your diet more environmentally friendly?

Did you identify how could you make sustainable change through your food intake? Remember,, the data needs to be interpreted carefully and, as Dr Rödl explained earlier, allowing for a significant error margin. In the original research that supported the carbon calculator the measure of ‘impact’ was constructed through the different food production methods that affect the overall kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions per serving of the food. The graph below shows the relative ‘impacts’ of different foods. It serves as an interesting summary of the dilemma of food sustainability we’ve been exploring. Take a close look at it. What strikes you about it?

Fig 15: The relative ‘impacts’ of food.

Source: Poore and Nemecek, (2018) reproduced by BBC, (2019)

The graph shows that a low impact beef might have been reared locally on a more sustainable diet than beef flown in from America fed on a high protein diet (remember Malte’s comment about the difference between free roaming grass fed beef and cattle reared in sheds). A chocolate bar made from cocoa imported from deforested rainforest could then have a higher impact through kilograms of greenhouse gas than locally reared beef. Conversely the highest impacting vegetable proteins have the same impact as the lowest impact animal proteins. It’s also interesting to see that beer has the same impact as dairy milk and that farmed prawns rank so highly in the number of kilograms of greenhouse gas emissions per serving. As Dr Rödl identified earlier, on top of this, there are further cultural impacts that have to be factored in such as land use, employment rights, production processes and so forth. Do any of these values surprise you? Having analysed your own diet, and perhaps thinking back to the role of plastics in food waste, would you make any changes to your consumption patterns?

In the next film Malte picks up on the question of cost, a vital element of the triple bottom line, as much for the consumer as for the producer.

How can we eat sustainably?

Dr Malte Rödl explains the decisions that he makes to eat more sustainably..

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

Food is a really good example of the tensions of sustainability. We have to eat. As Malte explains, when thinking about your food intake you have to make critical decisions around the sort of impact you want to make. The reference to cost is also interesting to consider here. Questions of sustainability have to factor in the pragmatics of cost; it can be more expensive, for example, to have biodegradable plates rather than styrofoam in a start-up street food business. Might a lower environmental impact be a ‘selling point’ to consumers who would then be willing to pay more? Similarly, it is more expensive to buy organic food. Is sustainability, then, a luxury available only to the more affluent? Or is it a case of going back to simpler values, eating locally grown food but in turn reducing the range of choice? Or is it about balance and eating less of the more environmentally damaging foods?

Both plastics and food highlight the need to think critically about environmental ‘greenwash’. As we have just discussed, if based on imported fruits, soy and meat substitutes, some vegan diets can have a massive carbon footprint, potentially rivalling that of a low impact beef diet. Likewise, not all plastics are the same. Then there is the need to factor in the broader context - there is little environmental benefit in driving to a further away shop because it has recycled bottles, for example.

Greenwashing, also known as ‘green sheen’, grew in popularity and use with the increasing environmental awareness of the 1990s. Sometimes greenwashing is a public relations or marketing exercise to make an organisation seem more environmentally friendly than they actually are, perhaps to enhance sales. Alternatively it can be used in an effort to disguise actively environmentally damaging activity. The term is also increasingly used to summarise grand claims about general aims or beliefs which are unsubstantiated, or worse, contradicted by action.

Further Study

This article from the Guardian provides an interesting historical overview of the term ‘greenwash’ and some intriguing examples, perhaps the most obvious being the multi million pound industry that is bottled water which, whilst healthier than other drinks, is massively unsustainable in its production and use and often drains already pressured natural resources to the expense of local people.

There is a growing body of literature dedicated entirely to how we communicate environmental messages, particularly around climate change. A tension lies in conveying sufficient scientific information to support an environmental claim, but in an accessible and relevant manner for the audience. It would be very difficult to summarise Professor Shaver’s thoughts about plastics on the back of a water bottle destined for sale in a supermarket, for example, or to enable national policy makers to truly understand how a late rainy season would impact a soy farmer in equatorial Africa (Chirisa et al., 2018). To make genuinely informed decisions about sustainability decisions, we need that critical knowledge.

With any environmental message it is important to think critically about its intention and aim. We use the term ‘critical’ a lot in academic writing and discussion. It does not necessarily mean to ‘rubbish’ the claim with critique (although you can, of course, disagree with it!), more to use it actively, thinking about the motives and aims of the message and how that impacts how it might be understood or used.

Generally the ‘Ws’, are a useful rule -

- Who wrote it?

- Why was it written?

- When was it written?

- Who was it written for?

- HoW was it written?

Being critical then, recognises that there are different viewpoints or positionalities in every discussion. This is why we will often ask you to ‘analyse’, ‘discuss’, ‘evaluate’ and so forth in discussions. Political viewpoints and the presentation of the same issue in different newspapers is the obvious example here. You might find that coming from different disciplinary backgrounds your thoughts are challenged by some of the sources in this course - perhaps you are a staunch scientist who believes in the epidemiology of disease over the social science of health, for example. Neither viewpoint is right or wrong, in fact together they paint a detailed picture to help us better understand illness but only if we understand the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

The two examples of plastics and food we’ve just looked at present the tension of the trade offs of economy, society and environment (profit, people and planet) in day to day decisions. A similar challenge applies for sustainable development of weighing up the merits of taxing cars to enter Manchester city centre, building a third pier on Manchester airport, imposing taxes on countries that are developing their industrial base and emitting carbon in the process. Every positionality, every viewpoint, every need will be different. This is where partnership is vital to achieve sustainable development, particularly through the SDGs.

1.4 SDG 17: Partnerships for sustainability and the SDGs

SDG 17: Partnership for the goals

Dr Jen O'Brien introduces Goal 17, Partnership for the Goals, and its role in achieving the other 16 SDGs.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

As explained in the film, to tackle sustainability problems we need new actors, often at different scales, working together in partnership. But who are these actors? What do they do? The next interactive draws upon your understanding of the challenges of the triple bottom line to unpack just that question – who is, or should be, responsible for tackling the sustainability challenges that we face today?

How did you rank the actors who should be responsible for sustainable development?

We asked Professor James Evans to rank his top actors most responsible for tackling the challenge of sustainability and explain why. There are no right and wrong answers to this exercise. One of the many beauties of interdisciplinary learning is that we all approach the same challenge from different perspectives and thus shed new light on old challenges. This was James’ ranking, and his explanation for it.

Whilst James listed business as, in his opinion, having top responsibility for sustainable development, note how his ranking illustrates partnership across and between sectors. People are the main driving force of business; Universities can support governments with knowledge. The UNFCCC meeting that we discussed earlier stressed the need for nations to work together to deliver on the mandates agreed in Paris in 2015. Partnership is the ethos of SDG 17. It is arguably the most important goal because it provides a blueprint for organisations and people around the world to be able to address the other 16 SDGs at whatever scale they can. This could range from international charities working with national governments to improve access to affordable vaccines (SDG 3: Health) to employees within an organisation working together to address gender inequality (SDG 5: Gender equality).

Fig 15: SDG 17

Source: UNHCC

When defining Goal 17, Partnership for the Goals, the United Nations state:

“The SDGs can only be realized with strong global partnerships and cooperation [......]

“The world is more interconnected than ever. Improving access to technology and knowledge is an important way to share ideas and foster innovation. Coordinating policies to help developing countries manage their debt, as well as promoting investment for the least developed, is vital for sustainable growth and development.”

United Nations

Drawing upon this description of SDG 17, in the next film Professor James Evans discusses the role of partnership in sustainability and, in turn, the role of SDG 17 in sustainable development.

Partnership Working

Professor James Evans discusses the role of partnership working for achieving the SDGs.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

Our ability to achieve the SDGs is underpinned by our ability to form effective partnerships. As James says in the film, there are numerous ways in which we can support the development of partnerships, including financial incentives, technology and capacity building. Remember how the COP offered additional support for capacity building to realise climate change policy. The final two ways to support partnerships are more about creating an enabling environment in which the SDGs can be effectively addressed, as James discusses in the next film.

Partnership Working

Professor James Evans continues his discussion of partnership working.

Trouble accessing? Please view on the UoM VideoPortal.

As James explains, technology, data and monitoring are examples of factors that can enable the delivery of the SDGs. In the next core module we will discuss more about the partnership required to fund the SDGs, which is estimated at $220-260 billion in international public finance. As James mentioned, digital technology is vital both to achieve the goals and to monitor their progress. Over 90% of the world’s data has been generated in the last two years often through new technology. Spatial data can play a critical role. For example, such data might map geographical locations of biodiversity, key watersheds, protected areas, human pressures and, as we will see later in this module in the case of Dr Jonny Huck’s GIS mapping tool, people requiring medical care, all of which enable policy makers to make better decisions and monitor progress towards the targets. Digital technology makes new forms of governance possible, bringing data and monitoring logics to the fore and connecting people, governments and resources in new and potentially more efficient ways (Trencher, 2018).